I have a problem with anger. It’s as simple as that. It’s a valid emotion and everyone gets angry, yes. But for me the lifelong challenge—it constitutes the majority of my time in therapy—is my reaction to anger. It’s what I do when I get angry, how I treat the people around me, and whether or not I am living according to my values that matters. Values like love, harmony, peace and kindness. Not anger, resentment, rage, and emotional reactivity, which I live with far too often.

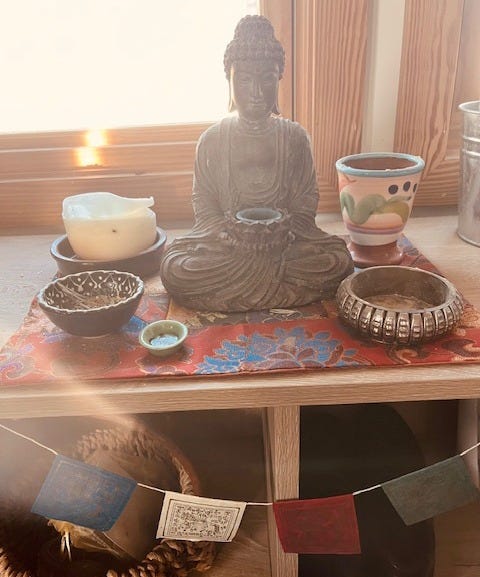

To that end, I’ve been working with mindfulness practices like yoga and meditation for more than two decades (three for yoga). I lived in Boulder, Colo., for twelve years which, if you know the area, you know is ground zero for alternative spiritual studies, meditation centers, the best yoga teachers and, interestingly, the original seat of Tibetan Buddhism in North America. I learned this fact while in graduate school in Boulder in the late 90’s-early 2000’s. You could say I found Buddhism there, in a difficult time in my life when I was looking for a spiritual home. Either that or I just stayed in Boulder long enough that I could no longer resist the pull of an incense-perfumed promise of inner contentment.

After the failed uprising of Tibet against China in the 1950’s, the Dalai Lama was exiled to India. While there, he sent Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a Tibetan Buddhist monk, to spread his teachings to the west. After studying in England and Scotland, Chogyam Trungpa gave up his monastic vows—apparently so he could teach his own version of Buddhism without all of the traditional trappings—and moved to the U.S. He ended up in Boulder (for reasons that are unclear but may have had something to do with the Beat Poets and the Zen teachers already there) where, in 1970, he started Shambhala International, an institution for teaching the priciples of Buddhism to Westerners. He also founded the Naropa Institute (now Naropa University), which became the first and only accredited Buddhist-inspired university in North America.

Chogyam’s teaching methods were sometimes controversial as was his personal life. (He died at age 47 from a heart attack). He was known for heavy drinking and sexual promiscuity which, in hindsight, may explain why he wanted to ditch the vows. He was a colorful, and complicated, and probably destructive too, human being. Definitely not the Dalai Lama. On the other hand, he is responsible for taking the often esoteric dharma (teachings) of Buddhism and making them contemporary and fresh, accessible to a much wider audience than he would have had as a monk in Tibet.

Anyway, while in graduate school my mom died and I went through a divorce. Then I got into a bad relationship. As many people do when going through a rough patch, I began to learn about mindfulness. I was in the right place, after all. I started by going to group meditation sessions at the Shambhala Center in Boulder—the one started by Chogyam Trungpa (when he wasn’t philandering) which was run by his former students. As I got close to completing my graduate degree, I was looking for something to do for myself as a treat. I learned about the Shambhala Mountain Center (now called Drala), a retreat center in the mountains outside of Fort Collins. I signed up for a five-day meditation retreat called “Turning the Mind Into an Ally” with Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, the eldest son of Trungpa and the heir of his lineage, also at that time, the Sakyong (leader). He, like his father, had some unconventional ideas about how to behave as a Buddhist monk in America. In 2018 he stepped back from leading the now international Shambhala organization after being accused of sexual misconduct.1 Oh, enlightenment. You do always come with a catch.

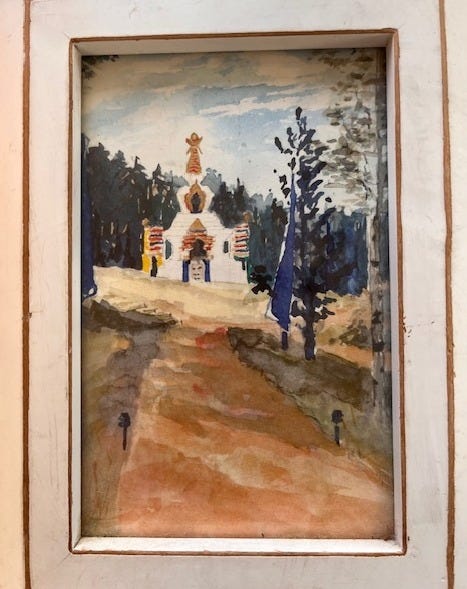

The retreat was not something I remember as being life-changing. But it was very transformational for me in the sense that I developed a deeper understanding of how meditation could be helpful to me not just in difficult times, but anytime and all the time. Each day we met under a huge tent to meditate and listen to talks and in our free time, hiked the grounds and visited the gigantic stupa, or temple, being constructed nearby. One afternoon I volunteered to serve tea to the Sakyong as a way to try and get a glimpse of this mysterious figure who seemed to be so unreachable. I think we spoke for a couple of minutes, I don’t remember about what. But I wrote an article about it for Elephant Journal (the old print version) so it must have left an impression on me.

***

Let me get back to how this relates to my ongoing challenges with anger. I’ve learned through therapy and countless examples from my own life that I have a part of me, an inner child perhaps, that gets angry, irate even, in order to protect me.2 Sometimes it’s because she feels like she is being ignored, or not listened to, or somehow persecuted by enemies real and imagined. She believes she is protecting me from harm because somwhere along the way —through some kind of trauma, or event, or maybe through the family or culture she grew up in—she learned that in order to keep me safe she had to yell and scream, to fight everyone she thought meant to hurt her, or maybe were hurting her emotionally or otherwise. Over and over this protective, well-meaning part produced a pattern in my life that was very destructive. This has been true in all of my relationships for as long as I can remember. It’s not so much with friends, but with those closest to me—my immediate family and family of origin.

One of the ways I am working on healing this inner child, this part of me, is through meditation. I am learning about Internal Family Systems, a therapeutic model that helps to “unblend” the various parts of ourselves—our inner critic or destructive part (some people call it addiction, or neurosis, or some other disparaging name), for me my “Angry part”—from the Self. In this way, we can begin a new relationship with that part and with ourselves, one that is more loving and compassionate, with the hope that this part can be liberated from the role it’s held for so long that has only led to suffering. This is the goal. The work takes time. And it’s hard. And at my age it seems like I would have this stuff all figured out by now. <Sigh> Instead, it feels like I’m only just beginning.

In my next post, I intend to write about some IRL examples of when my anger has gotten me into trouble, not just within my family but out in the world. Some of them are actually quite funny, stay tuned.

Leaving you with a quote by CTR, from one of his books that sit, dusty and unopened for so many years, on my bookshelves. I love the simplicity and unpretentiousness of his language.

Our opinions and attitudes about ourselves are very important. We cannot ignore the slightest tendency to feel wretched, inadequate, or fundamentally distrustful of ourselves. Those feelings always show through. This doesn’t mean that you are not allowed to think anything bad about yourself. However, there is another side of you that is an expression of goodness. This has to be recognized as well. Otherwise, without that nature of goodness, the human race wouldn’t be here at all. We would have destroyed ourselves a long time ago.

—Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

I experienced no creepy male behavior on the retreat, just to be clear.

This idea comes from the Internal Family Systems (IFS) model of healing trauma and specifically the book No Bad Parts by Richard Schwartz, Ph.D.

Thanks for sharing. Love you just the way you are❤️❤️❤️. And I learned some history of Buddhism in America.